Too Small To Succeed: Why Longmont's Revised Composting Facility Plan at the Distel Site Still Fails the Credibility Test

A Closer Look at the Design Flaws and the Overwhelming Contamination Risks

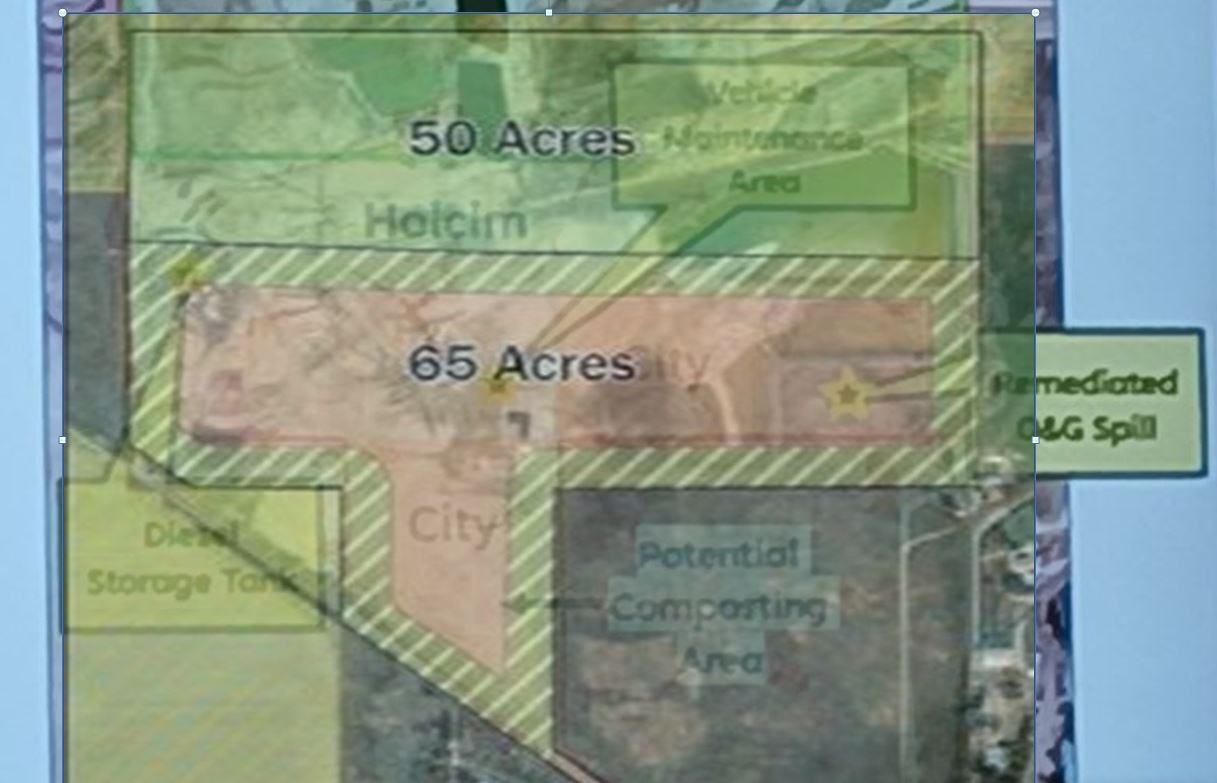

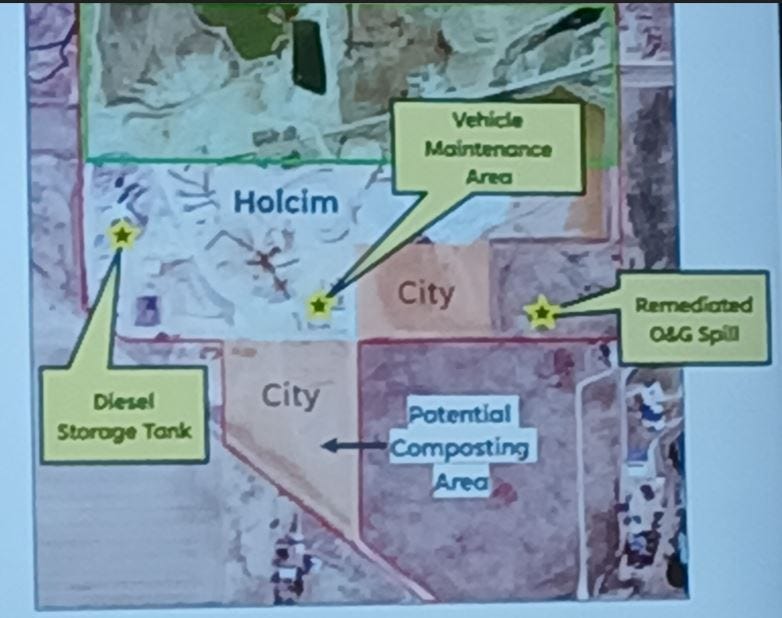

July 18, 2025 Update: A newly revealed map from City staff shows that the potential composting area is even smaller — much smaller — than previously known. After factoring in green buffer zones on 3 sides of the Distel property’s southern “City” peninsula, it’s only about 4 acres designated for composting.

NOTE: This article was written in June 2025. Please visit my new article, “🕳️ Underground Disclosure: The Shallow Groundwater Conundrum Threatening to Tank Longmont’s Composting Plan,” to read my new geotechnical analysis of the Distel property published on July 18, 2025.

🕳️ Underground Disclosure: The Shallow Groundwater Conundrum Threatening to Tank Longmont’s Composting Plan

Imagine Building Major Public Works on a Waterlogged Sponge

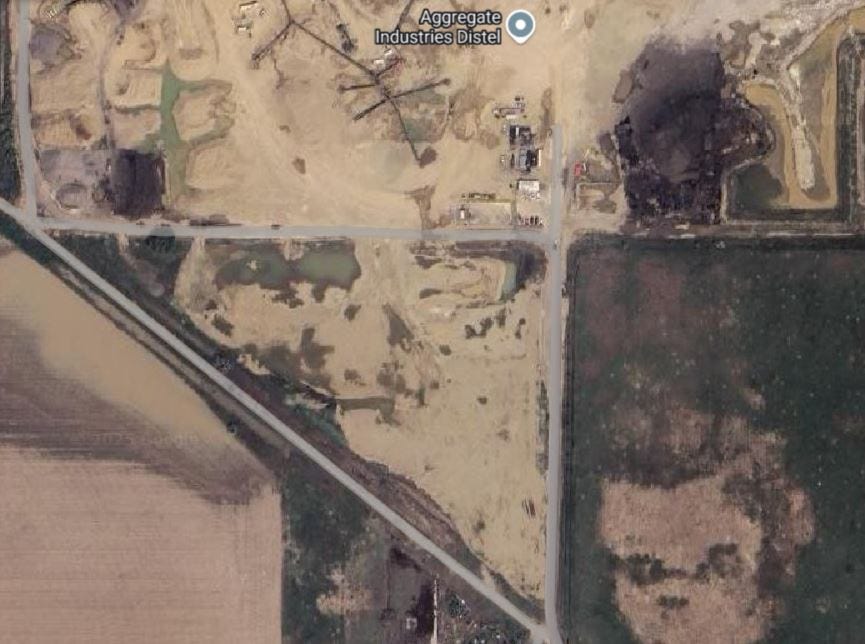

Longmont sits at a crossroads. On the table is a plan to reclassify the Distel property in Weld County—a 115-acre site with a long industrial history—into the home of a new, regional-scale composting facility. Local officials have pitched it as a sustainable way to process our organic waste. But beneath the green veneer lies a stark reality: the Distel site is too small, too contaminated, and too flawed in design to safely house such a massive operation.

Here’s why this matters.

The City of Longmont’s revised site plan has slashed the available working acreage from the original 115 acres down to less than 37 usable acres—thanks to a substantial green buffer zone and a critical road design flaw that swallows even more space. Worse yet, decades-old contamination at the site—including hydrocarbons and industrial runoff—would collide with the microplastics and heavy metals inevitably carried in by composting operations. This isn’t theoretical—it’s a documented risk supported by leading studies like Vithanage et al. (2021) and Okori et al. (2024). Together, they reveal how compost itself becomes a toxic conveyor belt for new pollutants that could reactivate old soil hazards—turning the Distel site into a poisoned well for Boulder County’s land and water.

This is more than just a local land-use debate. It’s a question of whether we’re willing to gamble with our environment, our health, and our community’s future—especially when smarter, safer alternatives exist. Let’s take a closer look at the facts that show why this project, as it stands, is simply too risky to proceed.

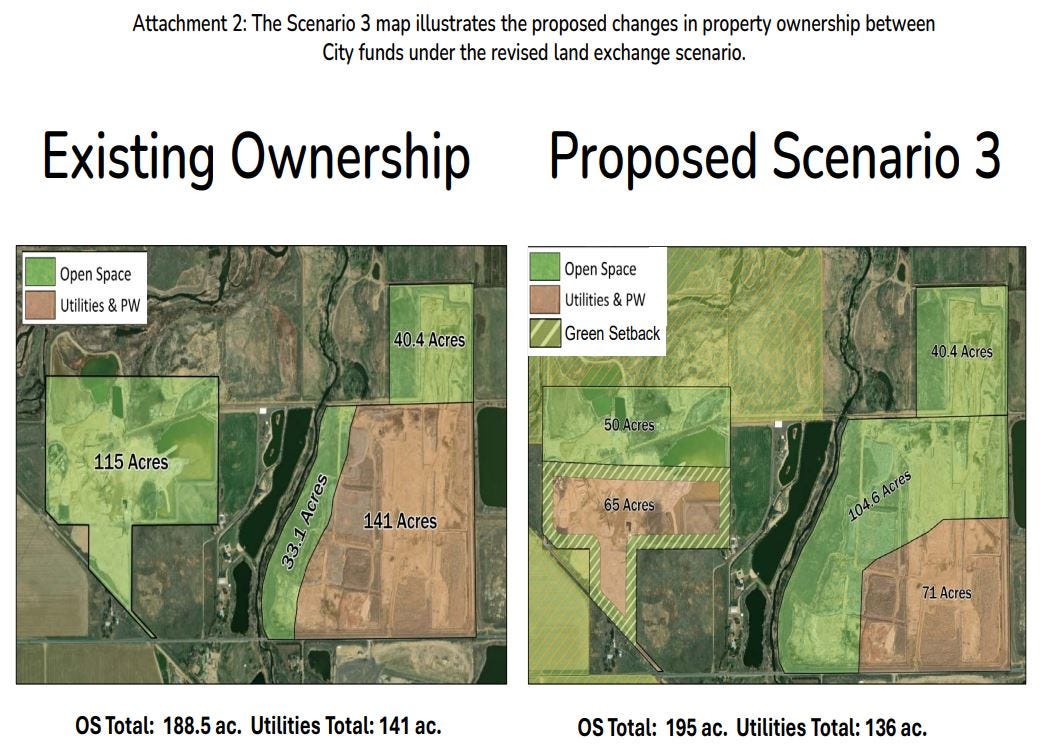

I. The Revised Plan in Context

Boulder County’s original concept (see below) for this composting facility was clear: transform the 115-acre Distel property into a robust regional-scale composting hub capable of handling 60,000–100,000+ tons of organic waste annually. In theory, this expansive property would provide ample room for everything needed: active composting, curing pads, equipment storage, traffic flow lanes, stormwater management, and the critical safety buffers demanded by an industrial-scale operation.

But the new plan put forward by the City radically shrinks that vision.

Under the updated site layout:

The northern 50 acres are set aside strictly as Open Space. No composting activities, no waste storage—only conservation land.

The southern 65 acres is the designated “working area” for the composting facility itself. But even here, not all of that land is usable.

The reason? The new plan (see below) imposes a large green setback zone—a perimeter buffer designed to separate the composting activities from neighboring uses. This buffer covers a significant portion of the 65-acre working area: ~28 acres, based on careful visual analysis of the revised site plan.

What does that leave?

Just ~37 acres of truly workable land for the entire composting facility. That’s less than one-third of the total property. And it’s a stunning 67% reduction from the original 115 acres once envisioned for this operation.

This severe downscaling poses unavoidable questions about feasibility and safety:

✅ Can 37 acres accommodate the processing, curing, and storage needs of 100,000+ tons of organic waste?

✅ Where will the stormwater ponds and leachate treatment areas go?

✅ How will traffic and heavy vehicle maneuvering fit within this squeezed footprint?

✅ Will the site be able to comply with Colorado’s mandatory setback and environmental protection regulations within such a constrained area?

The reality is: It can’t. And it’s not just a matter of convenience—it’s a matter of serious environmental, public health, and legal risk. In the next sections, we’ll dive deeper into the data—starting with the green setback zone itself—and show why the Distel site simply doesn’t measure up to the demands of a true regional composting hub.

II. Green Buffer Zone & Shrinking Footprint

The green setback zone—intended to reduce impacts on adjacent land and protect local environmental quality—might sound like a good idea on paper. But in reality, it carves away a staggering portion of the available space at the Distel site.

Let’s break it down:

🔎 Visual Overview:

On the revised site map, the 28-acre green setback zone wraps around nearly half of the 65-acre working area. What’s left—~37 acres—is squeezed into an awkward interior shape, hemmed in on all sides by this green belt.

🔎 Key Data Point:

Total working area: 65 acres

Green setback zone: ~28 acres

Usable land left: ~37 acres

This means that 43% of the designated composting area is now off-limits for any active composting use.

Why does this matter?

1️⃣ Composting Facilities Need Space

Regional-scale composting facilities like those in California (e.g., Jepson Prairie Organics, ~65 acres) and Oregon (e.g., Pacific Region Compost, ~80 acres) rely on large, contiguous footprints to safely and efficiently handle high volumes of organic waste. These operations include:

Active composting and curing pads

Heavy equipment maneuvering and vehicle access lanes

Stormwater basins and runoff control systems

Storage areas for finished compost, overs, and bulking agents

2️⃣ Industry Standard Land Requirements

Facilities processing 50,000–100,000+ tons annually typically require 50–80+ acres to function safely and meet environmental protection standards. The 37 acres left at Distel is simply not enough.

3️⃣ The Consequences of a Squeezed Footprint

Trying to cram such an operation into 37 acres is a recipe for:

🚫 Inadequate curing and storage capacity

🚫 Overlapping traffic and work areas—raising safety and accident risks

🚫 Poor air quality and dust control due to tight working zones

🚫 Insufficient room for buffer zones and environmental safeguards

🚫 Non-compliance with Colorado’s mandatory solid waste regulations (6 CCR 1007-2)

This is not just a theoretical concern. It’s a well-documented reality in the composting industry. Operations that underestimate spatial needs routinely face:

❌ Runoff and leachate management failures

❌ Regulatory enforcement actions and fines

❌ Community backlash and lawsuits over odor, noise, and health impacts

That’s why this 28-acre green setback zone—though environmentally well-intentioned—effectively destroys the feasibility of building a regional-scale composting facility on the Distel site.

III. Access Road Design Flaw

Beyond the space-squeezing green buffer zone, another serious design flaw has emerged in the revised Distel site plan: the existing main entrance to the property directly overlaps with the green setback zone itself.

This presents a significant logistical and environmental dilemma:

🚧 Road vs. Buffer Conflict

The access road—originally built to serve the aggregate mining operation—cuts straight through the 28-acre green buffer zone.

If the buffer zone is meant to protect nearby open spaces and sensitive lands, a road running right through it completely undermines that purpose.

Any compromise—such as waiving the buffer for the road—defeats the stated intent of green buffers to reduce traffic, noise, and pollution impacts on neighboring land.

🔎 No Room for Rerouting

Rerouting the access road entirely around the green setback would consume even more of the already limited 37 acres available for composting operations.

This further erodes the usable footprint for composting pads, curing areas, and critical infrastructure.

🔎 Costly Redesign, Delays, and Legal Headaches

Developing a new road that avoids the green buffer would involve:

✔️ Costly engineering work and land re-grading

✔️ Potential wetlands or stormwater permitting hurdles

✔️ Additional environmental review processesThe timeline for re-design and construction could add months—if not years—of delays, with significant new expenses for the City and taxpayers.

🔎 Regulatory Implications

Colorado’s 6 CCR 1007-2 solid waste regulations require clearly delineated and protected access routes to composting facilities—routes that cannot encroach on setback or buffer zones meant to protect environmental values.

💡 Bottom Line:

The access road’s overlap with the green buffer is not a minor planning oversight—it’s a fundamental design flaw that creates either:

❌ A direct violation of environmental standards, or

❌ A costly re-routing project that further slashes the already insufficient usable acreage.

This glaring inconsistency further proves that the Distel site is not suitable for a regional-scale composting facility.

IV. The Contamination Double-Whammy

Beyond the space constraints and road re-routing dilemma, there’s another looming threat at the Distel site—a dangerous contamination cocktail that makes the site wholly unsuitable for a large-scale composting operation.

🔎 Legacy Contamination from Industrial Use

The Distel property has a long history of aggregate mining and heavy equipment operations, leading to known contamination with diesel fuel, oil, and industrial runoff.

Brownfield conditions are already present, requiring substantial cleanup and remediation—costly undertakings that strain project feasibility.

🔎 New Compost-Borne Threats

Compost itself is a significant vector for microplastics (MPs) and heavy metals, as confirmed by recent peer-reviewed studies:

Vithanage et al. (2021) found ~1,000 microplastic particles per kilogram of compost, along with 1–10 mg/kg of toxic metals (Cr, Pb, Cu, Ni).

Okori et al. (2024) documented that composting processes can concentrate these contaminants, magnifying their presence in final compost.

At the scale proposed (60,000 tons/year), this would add:

✔️ ~54 billion microplastic particles annually to local soils

✔️ ~1,200 lbs of toxic metals/year, contaminating both compost and surrounding farmland

🔎 A Toxic Synergy

These new contaminants don’t just add to existing problems—they amplify them.

Microplastics and metals act as “sorption sponges”—they can bind to and mobilize legacy diesel and oil pollutants already in the soil.

This synergistic contamination creates a real risk of groundwater infiltration, crop contamination, and permanent soil damage.

🔎 Regulatory & Legal Ramifications

Colorado’s compost regulations under 6 CCR 1007-2 demand rigorous safeguards for sites with pre-existing contamination—including liners, leachate management, and enhanced stormwater controls.

The already cramped 37 acres cannot accommodate these advanced engineering controls—making regulatory compliance all but impossible.

💡 Bottom Line:

Siting a regional composting facility at Distel would be like pouring gasoline on a fire—stacking new compost-borne contamination onto an already hazardous brownfield.

It’s not just a local issue—it’s a serious risk to Boulder County’s agricultural future, water security, and community health.

V. Colorado’s Solid Waste Regulations Say No

While the City’s revised Distel plan is already hamstrung by size and contamination, Colorado’s own rules for composting operations make the fatal flaws even clearer.

🔎 Key Regulatory Requirements: 6 CCR 1007-2

The Colorado Solid Waste Regulations (6 CCR 1007-2) set out comprehensive standards for composting facilities, including:

✔️ Adequate setbacks from sensitive receptors like homes, schools, and waterways—typically 100 to 500 feet, depending on site conditions.

✔️ Engineered stormwater controls (e.g., impervious liners, leachate collection) to contain runoff and prevent groundwater pollution.

✔️ On-site environmental buffers and robust odor, dust, and noise mitigation plans.

✔️ Detailed site design and operations plans to ensure safe traffic flow, storage, processing, and curing areas—not squeezed into a patchwork footprint.

🔎 Why Distel’s 37 Acres Can’t Comply

Setbacks alone could consume 10–15% of the working land, reducing usable space even further—down to just 31–33 acres in a best-case scenario.

This leaves insufficient room for the required:

✔️ Compost processing and curing zones

✔️ Stormwater and leachate containment infrastructure

✔️ Buffer zones for noise and odor control

✔️ On-site access and maneuvering for heavy vehiclesWith no room left to accommodate these legally required components, the Distel site would likely fail state permitting standards outright.

🔎 Environmental and Legal Risks

Any facility that fails to meet these regulatory minimums risks fines, lawsuits, and operational shutdowns.

Siting the composting facility at Distel all but guarantees future violations of these standards due to spatial and contamination-related limitations.

🔎 Example of Compliance Gaps

Other successful regional composting facilities (like the Jepson Prairie Compost Facility in California, ~80 acres, and Pacific Region Compost in Oregon, ~90 acres) demonstrate what’s needed to comply with modern state and federal standards.

Distel’s 37 acres simply can’t replicate these proven models—there isn’t enough room for essential compliance infrastructure or best management practices.

💡 Bottom Line:

Under Colorado law, a regional-scale composting facility at the Distel property would be out of step with state standards from day one—making it a recipe for costly legal and environmental trouble.

VI. What’s at Stake for Boulder County

If the Distel composting facility moves forward despite these glaring flaws, Boulder County could face serious and lasting consequences:

🔎 Environmental Impacts

Groundwater contamination:

Legacy pollutants (diesel, oil, hydrocarbons) + new compost-borne microplastics and heavy metals = a dangerous cocktail that could infiltrate local aquifers and irrigation water supplies.Air quality degradation:

Composting operations release particulate matter and bioaerosols that, without proper buffers and control systems, pose a health risk to nearby residents and farmers.Soil health decline:

Ongoing deposition of microplastics and heavy metals can degrade soil structure, reduce agricultural productivity, and threaten regenerative farming efforts.

🔎 Community and Quality of Life

Noise and traffic congestion:

Increased heavy truck traffic and machinery noise from industrial-scale composting will affect rural tranquility and property values.Odor and dust nuisances:

Insufficient setbacks and operational space mean odor and dust controls will struggle to protect neighboring homes and schools.

🔎 Legal and Financial Risks

Non-compliance costs:

Violations of Colorado’s Solid Waste Regulations could result in substantial fines, lawsuits, and forced operational shutdowns—costs that would ultimately fall to taxpayers.Long-term liability:

If groundwater or soil contamination occurs, Boulder County and the City of Longmont could face decades of remediation obligations and reputational damage.

🔎 A Broken Promise of “Environmental Stewardship”

Boulder County has committed to environmental sustainability and responsible land stewardship. Pushing ahead with the Distel site flies in the face of those values—creating a real risk of permanent environmental damage at a site already burdened by decades of legacy pollution.

💡 Key Takeaway:

The Distel site isn’t just a suboptimal choice—it’s a threat multiplier for environmental and community harm. The decision to rezone and build here would betray Boulder County’s stated sustainability goals and expose residents to a host of avoidable risks.

VII. Better Alternatives Are Out There

The Distel site’s glaring design flaws, environmental risks, and regulatory hurdles make one thing abundantly clear: it is not the only option—and it is certainly not the right option.

🔎 Other Locations, Better Outcomes

Numerous sites in Boulder County and the broader region have been identified as more suitable for industrial composting:

Larger footprints: Sites with 80–120+ acres of workable land, not constricted by narrow buffer zones or legacy contamination.

Cleaner soils: Locations without historical diesel, oil, and chemical contamination, minimizing cumulative pollution risks.

Proximity to waste streams: Sites closer to major organic waste sources, reducing trucking miles and transportation emissions.

🔎 The County’s Responsibility

Boulder County’s zero waste and climate resilience goals require a composting solution that is robust, forward-looking, and environmentally sound.

Building on a small, contaminated site like Distel would lock in failure—wasting taxpayer money and harming the environment.

In contrast, a properly-sited composting facility can deliver genuine climate benefits by reducing landfill methane emissions and regenerating healthy soils.

🔎 Key Takeaway:

The choice is not “Distel or nothing.” The choice is whether to invest in a site that’s big enough, clean enough, and properly engineered to truly meet Boulder County’s needs—without harming our water, soil, and community health in the process.

Conclusion & Call to Action

The City’s revised plan for the Distel property—limited to 37 usable acres after green buffer zone setbacks—simply cannot house a regional-scale composting operation safely or sustainably. Coupled with legacy contamination, regulatory requirements, and costly design flaws, the project poses unacceptable risks to the environment, neighbors, and taxpayers.

💡 Top 10 reasons to oppose this project:

✅ Severe reduction in usable acreage – only ~37 of 115 acres workable.

✅ Green buffer zone further limits operations and heightens environmental stakes.

✅ Access road redesign creates new costs and threatens buffer zone integrity.

✅ Site’s contamination history (diesel, oil, industrial runoff) increases cumulative pollution risk.

✅ New microplastics and heavy metals influx would worsen legacy site pollution (Vithanage et al. 2021, Okori et al. 2024).

✅ Colorado’s solid waste regulations (6 CCR 1007-2) demand buffers, stormwater controls, and mitigation beyond what 37 acres can support.

✅ Risk of regulatory fines, legal challenges, and operational failures.

✅ Environmental harms: water, air, and soil contamination.

✅ Community impacts: noise, traffic, and health burdens.

✅ Other cleaner, larger, better-sited options exist.

📢 Join Us:

We urge the PRAB and County Commissioners to reject this ill-suited site for regional composting and pursue alternatives that are properly sized, clean, and capable of meeting Boulder County’s climate and waste diversion goals.

🔗 Take Action Today!

Submit your own public comments: Let PRAB and the County Commissioners hear your voice.

Contact local decision-makers directly: Share these facts and ask for responsible action.

Spread the word: Forward this analysis to your neighbors and networks to build collective power for change.