Longmont Council Selects Toxic Industrial Property in Weld County for Potential Composting Facility

The preliminary decision raises serious questions of negligence & incompetence by the City of Longmont in pursuing a composting facility at the Distel Property without adequate testing & remediation.

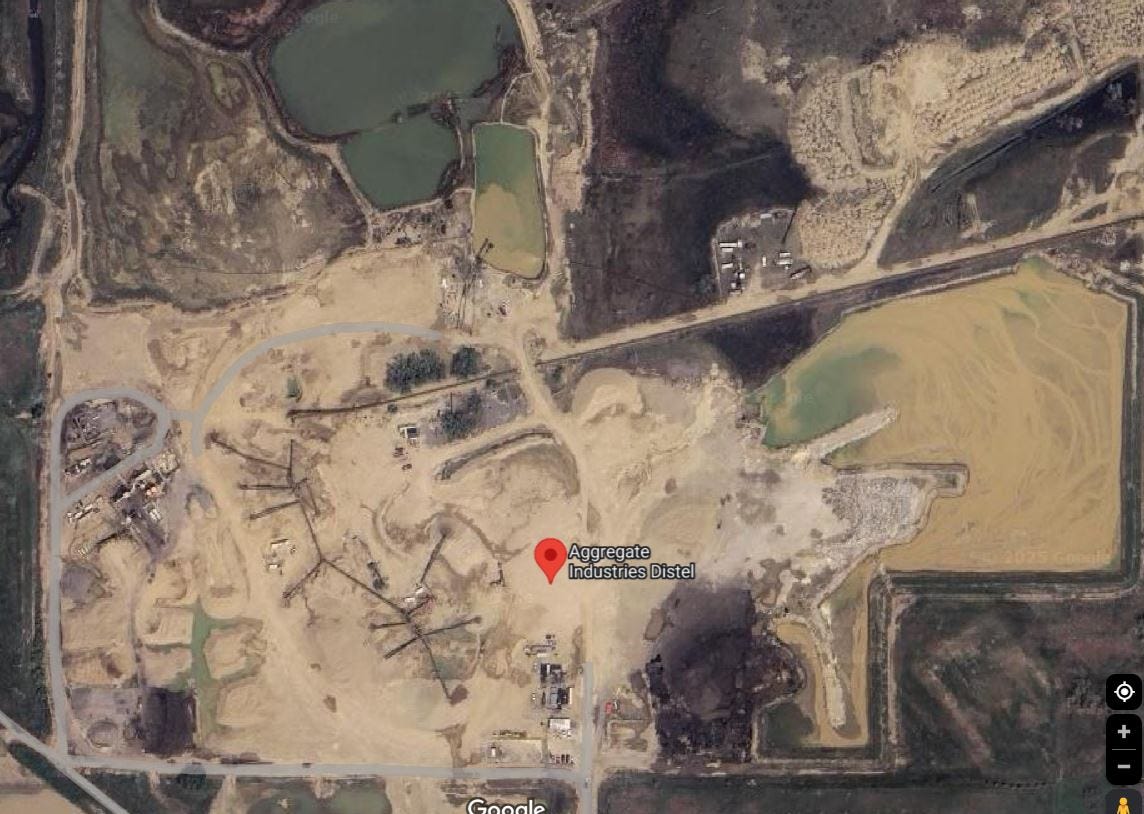

On Tuesday, January 14, 2025, Longmont City Council agreed to move forward with considering the possibility of pursuing a land swap that could eventually facilitate construction of a composting facility, in partnership with Boulder County, at a site in Weld County known as “Aggregate Industries Distel,” or “the Distel property” for short.

What is composting?

In simple terms a child could understand, composting is like making food for plants! Ideally, we take organic materials such as leftover food, leaves, and grass clippings and let them break down into dirt called compost. This compost is intended to help plants grow strong and healthy.

Why is it dangerous to do composting at a toxic site?

If we try to make compost on land that has harmful chemicals from a factory or industrial mining, those bad chemicals could get into the compost. Then, if people use that compost to grow food or flowers, the plants could absorb the chemicals, and that might make people and animals sick.

It’s like making a sandwich on a dirty, greasy table—no matter how good the sandwich ingredients are, the dirt and grease could make you sick. So, we need to make sure the land for composting is clean and safe before we start!

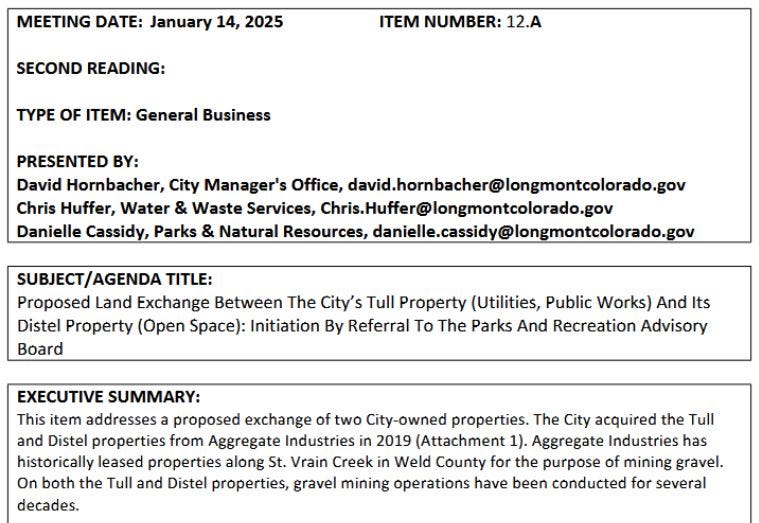

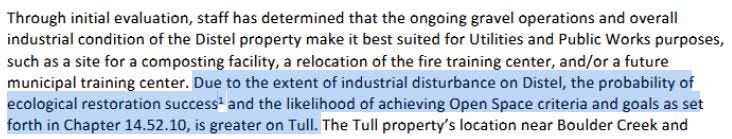

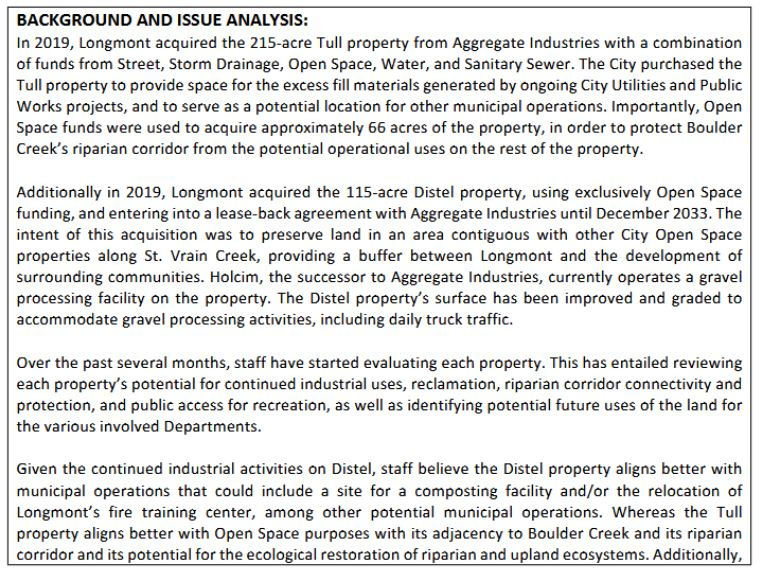

Longmont staff and council negligence put public health and safety at risk

City staff’s memo to council, presented by David Hornbacher, Chris Huffer and Danielle Cassidy, raised a gigantic red flag regarding the unsuitability of the industrial Distel site for a healthy and safe composting operation. “Due to the extent of industrial disturbance on Distel, the probability of ecological restoration success and the likelihood of achieving Open Space criteria and goals as set…is greater on [adjacent property] Tull,” they wrote. (In this context, “ecological restoration success” means restoring land to beneficial open space use by responsibly utilizing Open Space funding to restore ecosystems to a functioning state, i.e., creating native riparian and upland ecosystems that sustain native species and habitat.)

In other words, the extent of toxic pollution is so great from “industrial disturbance” that it would be difficult if not impossible to restore the property to a level of ecological integrity making it safe for public recreational access. But if the property is unsafe for public Open Space use, how can it be safe for composting? It’s not possible!

Before moving on to validate concerns about toxic contamination of the Aggregate Industries Distel site in more depth, let’s take a quick look at relevant parts of this staff memo:

(To read the full 3-page staff memo, turn to page 1318 in the City Council packet for the January 14, 2025 City Council meeting, which you can find in the Archived Meetings section of the City Clerk’s agenda management portal: https://longmontcolorado.gov/city-clerk/agenda-management-portal/.)

How can we determine if the Distel site is toxic?

A simple and affordable way to validate (or disprove) concerns about toxic pollution at this site would be testing the soil at multiple locations across the site. Representative soil sampling is like taking small scoops of dirt from different spots across the site to see if there are harmful chemicals hiding there. It’s a good way to check for toxic contamination because it gives us a picture of what’s happening in the soil across the whole area, not just in one spot. By testing these samples in a lab, we can find out if the soil is safe or if there are dangerous substances that need to be cleaned up before the site is used for a sensitive new purpose like composting.

But even without doing soil analysis, we can use deductive reasoning to reasonably conclude that concerns about toxic contamination at the Aggregate Industries Distel site are valid. First, the site has been characterized for years as a “Surface Metal Mine specializing in Construction Sand and Gravel,” according to MinesDatabase.com.

A typical surface metal mine specializing in construction sand and gravel involves industrial activities that can lead to several types of toxic contamination. The use of heavy machinery and equipment, along with the frequent presence of fuel storage and maintenance areas, often results in spills and leaks of diesel, gasoline, and lubricants, leaving behind hydrocarbons in the soil. Gravel processing, which may include the use of asphalt binders or additives, can contribute to contamination by polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs), which are toxic chemicals known to persist in the environment.

Additionally, the movement and wear of mining equipment and processing machinery can release heavy metals, such as lead, cadmium, chromium, and zinc, into the surrounding soil and water through runoff or dust. Sediment ponds used to collect runoff water can act as reservoirs for accumulated contaminants, which may leach into groundwater or nearby surface water bodies. If not properly managed, these contaminants can migrate off-site, posing risks to nearby ecosystems, agricultural lands, and human health. Dust and fine particulate matter from mining and stockpiling activities can also spread pollutants over a wide area, compounding the environmental risks associated with such operations.

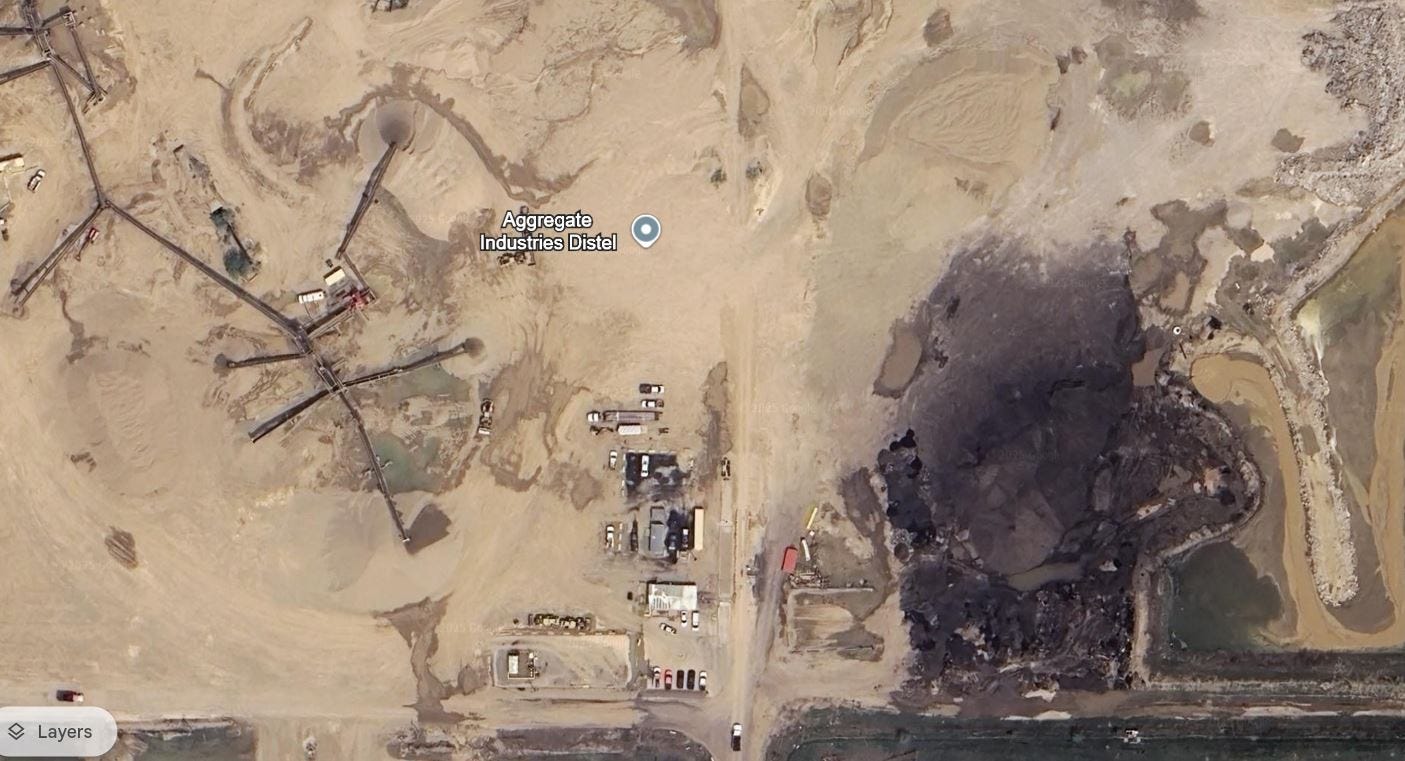

Next, we can utilize publicly available aerial imagery of the Distel site, from Google Maps and Google Earth, to assess the presence of toxic contamination. The first aerial photo included above is from Google Maps; here’s one from Google Earth:

The aerial photos of the Aggregate Industries Distel property and its surroundings provide crucial visual evidence of industrial disturbance and potential contamination. Based on these images, the following assessment highlights key observations and their implications for the presence of toxic contamination on the site.

Evidence of Industrial Disturbance

The aerial photos reveal a property heavily disturbed by industrial activities, including:

Dark-Stained Areas: Visible dark patches in multiple locations across the property suggest potential hydrocarbon spills or asphalt residue from equipment maintenance, processing, or vehicle operations.

Processing Zones and Stockpiles: The central area contains processing equipment and stockpiles of gravel, which are likely sources of fine particulate dispersion and chemical residue accumulation over time.

Sediment Ponds: Several large sediment ponds are present, appearing discolored and containing sediment. These ponds may act as sinks for runoff carrying hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and other pollutants from industrial operations.

Potential Sources of Contamination

Based on the visible evidence, the likely sources of contamination include:

Hydrocarbons: Leaks or spills from heavy machinery and vehicles may have introduced petroleum products into the soil.

Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds (PACs): Asphalt-related activities, such as storage and processing, can release toxic PACs into the environment.

Heavy Metals: Dust and runoff from machinery, stockpiles, and sediment ponds may contain metals such as lead, cadmium, and chromium, which can accumulate in the soil and water.

Proximity to Sensitive Areas

The photos show the property’s location relative to surrounding ecosystems and human activities, highlighting additional concerns:

Boulder Creek: Located near the property, Boulder Creek could receive runoff from the site, spreading contaminants into riparian ecosystems and downstream water bodies.

Agricultural Land: Adjacent farmland to the south and east may be at risk of contamination from airborne dust or water runoff, threatening crop safety and soil health.

Runoff and Drainage Pathways

The aerial photos suggest visible pathways where water and sediment may flow:

Runoff from industrial areas is likely directed toward sediment ponds or into surrounding ditches, potentially carrying contaminants beyond the site boundaries.

The proximity of disturbed land to natural waterways raises concerns about contamination spreading into surface and groundwater systems.

Impact of Ongoing Industrial Use

The site is actively used for gravel processing and daily truck traffic, as evidenced by the operational equipment and visible wear on the land. Continued industrial activities can exacerbate existing contamination, further deteriorating soil and water quality.

Limitations of Restoration Potential

The extensive grading and industrial disturbance visible in the photos suggest that restoring the site to natural Open Space standards would be challenging. The level of soil disturbance and potential for deep contamination likely require significant remediation efforts before the property could safely support alternative uses.

The aerial photo analysis provides compelling evidence of potential toxic contamination on the Aggregate Industries Distel property. Dark-stained areas, sediment ponds, processing zones, and visible runoff pathways highlight risks of hydrocarbons, PACs, heavy metals, and fine particulate contamination. The property’s proximity to Boulder Creek and agricultural lands amplifies these concerns, as contaminants could spread beyond the site, affecting ecosystems, water quality, and public health.

This analysis underscores the urgent need for comprehensive soil, water, and sediment testing to quantify contamination levels. Without such assessments and subsequent remediation, the property is unsuitable for activities like composting, which require uncontaminated land to protect public health and environmental integrity. The visual evidence reinforces the recommendation to reject the proposed siting of a composting facility on this property and prioritize alternative, cleaner locations.

Further validating these concerns, multiple EPA incident reports for the Aggregate Industries site highlighted the presence of concerning toxic substances linked to historical industrial activities. Two reports filed in 2006 under the facility's Toxic Release Inventory (TRI), for example, identified contaminants and potential pathways for environmental harm. EPA reports for contamination incidents at the Distel property were also filed for the same chemicals in 2002 (Benzo / PACs), 2004 (Benzo / PACs), 2005 (Benzo / PACs), 2007 (Benzo / PACs) and 2008 (Benzo / PACs). Below is a summary of key findings and their implications for using the property as a composting facility in 2025 and beyond.

Contaminants Identified

The EPA reports documented the presence of:

Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds (PACs):

These toxic, long-lasting chemicals are associated with asphalt and petroleum products used in gravel and sand mining operations.

PACs are known to cause severe health and environmental effects, including carcinogenic risks, ecosystem disruption, and soil contamination.

A specific PAC identified on-site, known for its persistence in the environment and toxicity to aquatic life.

This compound typically accumulates in sediments, posing risks to both soil and nearby waterways.

Sediment and Dust Pathways:

Fugitive emissions of dust and sediment containing PACs and other potential contaminants were noted, indicating risks of airborne dispersion and runoff into surrounding ecosystems.

Contamination Pathways

The EPA Reports provide limited but important information regarding the land disposal of polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) and Benzo[g,h,i]perylene at the Distel property. Here is a detailed breakdown of the relevant sections.

Land Disposal Pathways and Methods

RCRA Subtitle C Landfills:

The facility may have used RCRA Subtitle C Landfills, which are designated for hazardous waste disposal. These landfills are engineered to meet strict standards, including leachate collection systems, liners, and groundwater monitoring. However, no specific quantities of PACs disposed of via this method are reported in the document.

Other Landfills:

Disposal in non-hazardous landfills is indicated as a possibility. This could involve PACs being treated as non-hazardous waste under certain conditions, which may pose a risk if containment and monitoring are inadequate.

Land Treatment/Application Farming:

The report lists land treatment or farming as a potential disposal method. This involves spreading waste on land and relying on natural degradation processes, such as microbial activity. While effective for organic wastes, this method is inappropriate for persistent and toxic compounds like PACs, as it could lead to contamination of soil and groundwater.

Surface Impoundments:

Surface impoundments are areas where liquid or slurry waste is stored in open ponds. These are typically unlined or poorly lined, increasing the risk of leachate entering the subsurface and contaminating groundwater. PACs disposed of in this manner may also volatilize into the air or accumulate in sediments, posing long-term risks.

Other Surface Impoundments:

The report differentiates between primary surface impoundments and “other” types, possibly including unregulated ponds or basins. These might lack the engineering controls found in compliant surface impoundments.

Other Disposal:

This category is ambiguous and may include dumping, burying waste, or other unregulated methods. The absence of details raises concerns about potential gaps in regulatory oversight.

Environmental Risks of Land Disposal

The use of these methods for PAC disposal carries significant environmental and health risks:

Soil Contamination:

PACs can bind to soil particles, remaining persistent and toxic for long periods. This creates a long-term risk of contamination to surface soil layers, affecting plants and animals.

Groundwater Contamination:

Improper disposal, particularly through surface impoundments or unlined landfills, could allow PACs to leach into groundwater. PACs are hydrophobic but can still migrate under certain conditions, especially when dissolved in organic solvents or emulsified.

Bioaccumulation:

PACs can accumulate in organisms and move up the food chain, posing health risks to wildlife and humans through contaminated water or food sources.

Air Emissions:

Surface impoundments or land treatment might facilitate the volatilization of lighter PAC components, contributing to fugitive air emissions and air quality concerns.

Implications for a Composting Facility in 2025

Using this site as a composting facility poses severe challenges due to its contamination history:

Health Risks:

Composting involves biological processes that rely on clean, healthy soil. If contaminants like PACs or heavy metals leach into compost, they could be absorbed into organic material, rendering it unsafe for agricultural or landscaping use.

Exposure to toxic dust and VOCs during composting operations could harm workers and nearby residents.

Environmental Risks:

Leachate from compost piles could carry contaminants into the soil or sediment ponds, worsening existing pollution.

Runoff into Boulder Creek could have cascading effects on aquatic ecosystems and downstream water quality.

Regulatory Concerns:

Composting facilities are subject to strict environmental standards to ensure the safety of the compost and prevent harm to surrounding areas. The presence of known contaminants could make it difficult to meet these regulatory requirements, leading to potential legal and operational issues.

Operational Challenges:

Remediation efforts would likely be required before the site could be deemed suitable for composting. These efforts would be costly, time-consuming, and could delay the project's implementation.

Has Toxic Contamination Continued Post-2008?

The EPA contamination reports from 2002 to 2008 confirm the presence of toxic substances on the Aggregate Industries Distel property, including PACs and Benzo[g,h,i]perylene, which are known to pose significant health and environmental risks. These findings, combined with the visible industrial disturbance and contamination pathways observed in aerial photos, validate concerns about the site's unsuitability for a composting facility in 2025 and beyond. Six years of EPA reports for contamination incidents at the Distel property were filed for each of these two chemicals. It’s crucial to understand that annual EPA contamination reports typically summarize the total releases or incidents of toxic chemicals over an entire year, not just a single incident on one specific day. This means that a single annual report for a substance like polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) or Benzo[g,h,i]perylene could account for multiple instances of release or ongoing emissions throughout the year.

In addition, the cessation of Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) reports for the Distel property after 2008 raises significant concerns about the potential continuation of toxic contamination despite the absence of documented disclosures. TRI reporting requirements are stringent but not universal, applying only to facilities that meet certain thresholds, such as employing 10 or more full-time employees or processing specified quantities of toxic chemicals. If the Distel property’s employee count fell below this threshold, the site could have legally ceased filing TRI reports, even if operations involving hazardous substances continued. This loophole means the absence of TRI filings is not conclusive evidence of a clean or safe site; rather, it highlights a gap in oversight for small-scale industrial facilities that could still pose substantial environmental risks.

Historical TRI reports from the property, particularly those documenting the release of polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) and other hazardous chemicals, indicate a long-standing pattern of toxic contamination. These contaminants, including heavy metals and PACs, are persistent in the environment, often binding to soils or leaching into groundwater. The lack of post-2008 reporting does not necessarily reflect a cessation of these releases but could instead signify a decline in the facility’s operational scale, allowing it to avoid reporting obligations. Small industrial sites, particularly those with fewer employees, are notoriously under-monitored, leaving the potential for ongoing contamination unchecked. Without systematic environmental testing, it is impossible to determine whether harmful discharges ceased or merely continued without formal accountability.

Moreover, the aerial imagery of the Distel site suggests ongoing industrial activity well after 2008, with visible signs of deterioration, such as expanding disturbed areas, darkened soils, and pooling water that may indicate runoff or drainage issues. These visible changes are consistent with sites where contamination persists or worsens over time. Given the nature of the operations historically conducted at the Distel property—mining, asphalt production, and material processing—it is plausible that toxic chemicals continued to be handled, stored, or inadvertently released, even at reduced production levels. The absence of TRI reporting leaves a critical gap in our understanding of how these activities may have impacted soil and groundwater quality over the last 15 years.

It is also important to recognize that PACs and other contaminants previously reported at the site are often associated with long-term environmental and public health risks. PACs, for instance, are known to bioaccumulate and persist in ecosystems, posing dangers to both humans and wildlife. If ongoing operations, even at a reduced scale, involved the movement, storage, or processing of materials containing these compounds, the risks of contamination remain high. The historical pattern of releases, combined with the apparent reduction in oversight after 2008, raises serious questions about whether the site was managed responsibly in subsequent years. Without TRI reports or independent soil and water testing, there is no way to definitively confirm that harmful releases did not continue.

Therefore, the cessation of TRI reports for the Distel property after 2008 should not be interpreted as evidence that the site is free from contamination. Instead, it highlights a significant regulatory blind spot that could have allowed toxic releases to continue unmonitored. The aerial evidence of ongoing activity and deterioration, coupled with the historical presence of hazardous substances, underscores the urgent need for comprehensive soil and groundwater testing to assess the site’s current condition. The reliance on employee count or production thresholds to determine reporting obligations creates an unacceptable gap in oversight for small industrial facilities, leaving communities vulnerable to unchecked environmental harm. It is imperative that caution be exercised before repurposing this site for a composting facility or any other use that could exacerbate or spread existing contamination.

Given these factors, the City of Longmont should prioritize thorough environmental assessments and remediation before considering any development on this site. Additionally, alternative locations should be explored for the composting facility to ensure public health, environmental safety, and regulatory compliance.

A Scathing Indictment of Negligence and Incompetence by the City of Longmont in Pursuing a Composting Facility at the Distel Property Without Adequate Testing and Remediation

The City of Longmont’s preliminary decision to move forward with plans to site a composting facility at the toxic, industrially disturbed Aggregate Industries Distel property without conducting comprehensive environmental testing and remediation is a glaring example of gross negligence and incompetence. This action undermines public trust, endangers community health, and disregards fundamental environmental stewardship responsibilities. The failures of City staff and Council to prioritize safety and due diligence in advancing this proposal highlight an alarming level of irresponsibility.

The Distel property’s long history of industrial use, including gravel mining, asphalt processing, and heavy machinery operations, has left an undeniable legacy of contamination. Reports from the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory and visual evidence from aerial photographs underscore the high likelihood of toxic substances, including hydrocarbons, polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs), and heavy metals, polluting the soil and water. These contaminants are well-documented to pose serious risks to human health and environmental integrity, yet the City has chosen to ignore these warnings. The absence of a thorough environmental assessment demonstrates either willful ignorance or a reckless disregard for the well-being of Longmont’s residents and ecosystems.

What is most egregious is the City’s insistence on pursuing a composting facility on such a compromised site. Composting relies on clean soil and water to produce safe, usable materials for agriculture and landscaping. Siting a facility on contaminated land risks leaching toxic substances into the compost, rendering it unsafe and potentially harmful. This decision not only endangers workers and nearby residents but also jeopardizes downstream ecosystems such as Boulder Creek, which could receive runoff laden with pollutants. The failure to address these concerns reflects a shocking lack of competence and foresight on the part of decision-makers.

The City’s handling of this issue has also been marked by a disturbing lack of transparency. Residents have not been adequately informed about the site’s contamination risks, nor have they been given an opportunity to adequately weigh in on the decision-making process, although a public hearing by the City’s Parks and Recreation Advisory Board (PRAB) is required to be held within 60 days after Council’s decision to refer the issue to PRAB. By withholding critical information and failing to honestly engage the public, the City has breached its ethical obligation to act in the best interests of the community. This disregard for accountability further erodes trust in local governance.

Should contamination from the Distel property harm residents, workers, or the environment, the City could face serious legal and financial consequences. Lawsuits from affected individuals or regulatory agencies, as well as fines for noncompliance with environmental standards, would burden taxpayers and strain municipal resources. These risks far outweigh any perceived benefits of rushing this ill-conceived project forward without proper due diligence.

To rectify this negligence, the City must immediately halt plans for the composting facility at the Distel property. Comprehensive soil, water, and sediment testing must be conducted to fully understand the extent of contamination. If the site is found to be unsuitable, alternative locations must be identified that do not pose such significant risks to public health and safety. The City must also commit to transparency by sharing all findings with the public and engaging residents in future decision-making processes.

The City of Longmont’s pursuit of a composting facility at the Distel property without addressing these critical concerns is a blatant failure of responsibility. This negligence places public health, environmental integrity, and the City’s reputation at significant risk. It is imperative that the City corrects course immediately to uphold its duty to protect the community it serves. Failure to correct course should result in the recall petition and ultimate removal of all elected officials responsible for this travesty and the firing of senior staff who pushed it forward.

Regulatory Oversight

In Colorado, the establishment and operation of composting facilities are primarily regulated by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) under the Colorado Solid Waste Regulations, specifically 6 CCR 1007-2, Section 14. These regulations classify composting facilities into different categories (Class I, II, III, etc.) based on factors such as the types and volumes of feedstocks processed. Each class has specific requirements for design, operation, and permitting. For instance, Class II facilities must develop an Engineering Design and Operations Plan (EDOP) that demonstrates how the facility will prevent negative impacts to surface water and groundwater, among other criteria. (CDPHE Solid Waste Regulations)

At the county level, both Boulder and Weld Counties have additional permitting processes. In Boulder County, any commercial compost facility must obtain a Special Use permit through the Boulder County Community Planning & Permitting Department. This process involves comprehensive site design, engineering review, and environmental impact studies to mitigate potential impacts before permit issuance. (Boulder County Compost Facility FAQs)

In Weld County, the siting and permitting of solid waste disposal sites, including composting facilities, involve dual jurisdiction between the CDPHE and Weld County authorities. The primary regulations are outlined in the Colorado Regulations Pertaining to Solid Waste Disposal Sites and Facilities (6 CCR 1007-2). Weld County's specific requirements are detailed in Section 23-4-380 of the Weld County Code. For certain uses, such as organic fertilizer production and composting facilities, applicants must follow the "Use by Special Review" (USR) procedural guide, which includes submitting detailed plans and undergoing a review process. (Weld County Waste Program / Weld County USR Procedural Guide)

Comparatively, the permitting processes in both counties require thorough reviews to ensure environmental protection and community safety. While specific procedural differences exist, both counties mandate comprehensive evaluations, and neither offers a significantly "easier" permitting pathway for composting facilities. Therefore, operators should be prepared to meet stringent requirements in either jurisdiction.

However, Boulder County Commissioner Ashley Stolzmann’s public testimony in favor of the project raises questions about why an elected official in Boulder County wants to locate this composting facility on toxic land in Weld County. “We think this is a great partnership opportunity. I look forward to collaborating with Longmont and being a part of the county’s own effort at making this significant move towards zero waste,” Stolzmann reportedly said.

Preliminary Soil Analysis

A 1995 soil description that Weld County presented prior to the onset of mining highlights the significant vulnerabilities to toxic contamination at the Distel property after decades of surface mining and its potential for environmental remediation. Here’s an in-depth analysis:

Vulnerability to Toxic Contamination

Poor Drainage and High Water Table:

Aquolls and Aquerts soils are characterized by poor drainage and a high water table during spring and irrigation seasons. These features make them highly susceptible to contamination because toxic substances from surface mining, such as hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and other pollutants, can persist in poorly drained soils and infiltrate the groundwater.

The gleyed layer in some areas indicates water saturation, which can further exacerbate the leaching of contaminants into the water table.

Proximity to Water Sources:

The soils' location in natural drainage ways and depressions amplifies the risk of contamination spreading. Any toxins introduced through mining activities could easily migrate into surrounding water systems, including runoff into irrigation channels or nearby waterways.

Salinity and Alkalinity:

Farming and irrigation in adjacent areas have already increased salinity in the soils, a condition exacerbated by mining activities. Salts can act as carriers for toxic substances, increasing the mobility of pollutants.

Erosion and Soil Blowing:

Sandy loams like Olney fine sandy loam and Vona sandy loam are prone to erosion and soil blowing, particularly when vegetation is removed or disturbed. Dust and particulate matter from mining can spread contaminants over wide areas, including nearby agricultural fields and residential zones.

Rapid Permeability:

The Vona sandy loam and parts of the Olney soils exhibit moderate to rapid permeability in the subsoil, increasing the risk of contaminants quickly percolating through the soil profile to groundwater. This is particularly concerning for the surrounding agricultural and urban areas.

Challenges to Remediation

Depth of Soil Contamination:

These soils were described as deep (60 inches or more) and well-developed in 1995, possibly making it challenging to identify and remove contaminants thoroughly. The effort required to address contamination throughout the entire soil structure, including surface layers and substratum, would likely be extensive and costly.

Salt and Alkalinity Management:

The accumulation of salts and alkaline conditions complicates remediation efforts. These conditions can make chemical treatments less effective and reduce the viability of native or introduced vegetation for ecological recovery.

Wetland Restoration:

Restoring wetland areas associated with Aquolls and Aquerts soils, which are critical for waterfowl and other wildlife, would require careful reestablishment of hydrological conditions. Contaminants could persist in water-saturated soils, making wetlands a reservoir for toxins.

Vegetative Recovery:

Although species like switchgrass, big bluestem, and western wheatgrass are suitable for reseeding, the success of revegetation depends on eliminating contaminants and undesirable vegetation first. Without comprehensive cleanup, plants may uptake toxic substances, posing risks to wildlife and potentially human food systems.

Urban Development Limitations:

For Olney and Vona soils, their potential for urban development is limited by the hazard of groundwater contamination from toxic substances. The rapid permeability of these soils exacerbates the risk of spreading pollutants from industrial or residential activities.

Insights for the Distel Property

After decades of surface mining, the Distel property’s soils are highly vulnerable to contamination. The challenges include groundwater contamination risks, the persistence of pollutants in poorly drained or rapidly permeable soils, and the complexity of restoring these soils to a state suitable for reuse.

The likelihood of successful remediation and ecological recovery hinges on:

Comprehensive soil and groundwater testing to determine the extent of contamination.

Thorough removal or stabilization of contaminants.

Hydrological and vegetative restoration tailored to the site’s specific soil conditions.

Without such measures, converting the property into a composting facility risks further contaminating the soils, adjacent lands, and water systems. This analysis underscores the need for exhaustive environmental assessments and remediation plans before pursuing any redevelopment.

Close Up 2023 Aerial Photo Analysis

Finally, we’ll wrap up this article with deeper analysis of four of the worst-looking sections of this property in terms of likely toxic contamination.

This aerial photo shows a close-up of the southwest corner of the Distel property, revealing details of its surface conditions and activities. Here is an analysis of the site based on the visual data:

Observations from the Image

— Surface Activity

The image shows areas of active or recent excavation, indicated by exposed soil and varying shades of earth materials. These features suggest ongoing or historical material stockpiling and excavation operations.

The presence of machinery (visible in the center-right) indicates continued industrial use, possibly for aggregate processing or material handling.

— Darkened Areas

Several darkened patches, particularly in the center and lower-left portions of the image, may represent:

Accumulated industrial byproducts (e.g., asphalt, coal dust, or other hydrocarbons).

Soil contamination from past or current spills or leaks, particularly if these areas are not naturally wet.

Stagnant water or materials leaching from stockpiles, possibly contributing to contamination risks.

— Greenish Pools

The greenish areas to the upper-right suggest pooled water or possible slurry from industrial operations. These pools raise concerns about:

Potential leachate contamination carrying heavy metals, PACs, or other pollutants.

Water accumulation in low-lying areas, which may facilitate contaminant migration into the groundwater or surrounding ecosystems.

— Stockpiles

Visible mounds suggest material storage, which could include processed aggregates, overburden, or waste materials. Stockpiles, especially when exposed to weather, can contribute to runoff contamination.

Risks Highlighted by the Image

— Contamination Pathways

The surface features suggest several potential pathways for contamination, including:

Runoff: Rainwater or melting snow could carry contaminants from stockpiles and exposed soils into surrounding waterways.

Groundwater Infiltration: Permeable soils, as identified in previous soil analyses, may allow contaminants to leach into the water table.

Airborne Dust: Wind erosion of exposed materials may spread fine particles, which could include heavy metals or hydrocarbons.

— Hydrocarbon and Heavy Metal Risks

The darkened areas and machinery operation suggest potential spills or leaks of hydrocarbons (e.g., diesel, hydraulic fluids) and heavy metals from equipment wear.

Such contamination could have long-term environmental impacts, particularly if not adequately contained or remediated.

— Water Quality Concerns

The greenish pools could indicate water stagnation or contamination by industrial runoff. Without proper water quality testing, the risk of these pools serving as contamination reservoirs remains high.

Implications for a Composting Facility

Based on this image:

Risk of Soil and Water Contamination: The visible signs of industrial activity, pooled water, and darkened areas suggest existing contamination, which could compromise compost quality.

Costly Remediation Requirements: To ensure suitability for composting, extensive soil testing and potential remediation would likely be necessary to address contamination risks.

Environmental Liabilities: Operating a composting facility in this environment could lead to unintended consequences, such as the mobilization of contaminants through water or soil disturbance.

Recommendations

Comprehensive Site Testing: Perform targeted soil and water testing at visible darkened areas, stockpiles, and pools to identify contaminant levels.

Containment Measures: Implement barriers or cover systems for exposed materials to prevent runoff or leaching during rainfall.

Environmental Assessment: Conduct a detailed environmental impact study before any development to understand the full scope of contamination risks.

This photo reinforces previous concerns about the Distel property's suitability for a composting facility. Without significant remediation, the risks of contaminant migration and environmental harm remain substantial.

Located due north from the previous photo, this aerial image offers a closer view of an industrial facility on the Distel property, likely focusing on aggregate processing and related activities. Here’s a detailed analysis of the site based on the visual data:

Observations

— Industrial Infrastructure

Visible Machinery and Structures: The image highlights several pieces of machinery, pipelines, storage tanks, and buildings, indicative of aggregate processing operations. These structures may handle tasks such as crushing, washing, and storing materials.

Storage Tanks: The presence of multiple storage tanks suggests potential storage of fuel, chemicals, or process water. This raises concerns about spills or leaks over time.

Conveyor Systems: The numerous conveyor belts stretching across the site are indicative of large-scale material handling and sorting operations.

— Surface Conditions

Dark Stained Areas: These areas likely indicate spill zones or accumulation of industrial residues, potentially hydrocarbons or other byproducts of aggregate processing.

Bare and Disturbed Earth: Much of the surface is devoid of vegetation, with signs of excavation and material displacement. This makes the site vulnerable to erosion, dust dispersion, and leaching of contaminants.

— Water-Adjacent Features

Pond or Lagoon-like Area: To the left-center of the image, there appears to be a water or slurry pond. This could be a settling pond for runoff or process water, possibly contaminated with silt, heavy metals, or other pollutants.

— Vehicle Presence

Several vehicles and industrial trucks can be seen, underscoring ongoing activity. Vehicle operations contribute to potential contamination through fuel and oil leaks.

Environmental Risks

— Contamination Pathways

Surface Spills and Runoff: The stained areas and water-adjacent features highlight the risk of surface contaminants entering local water systems or seeping into the soil.

Airborne Dust: Exposed soil and operational machinery can generate dust that may carry particulates, including heavy metals, PACs, and silica.

Groundwater Infiltration: If the subsurface geology is permeable, leachate from the site could migrate into aquifers, impacting groundwater quality.

— Storage Tanks

Leakage Concerns: Storage tanks might contain fuels, lubricants, or process chemicals. Without secondary containment measures, leaks could significantly contaminate the surrounding soil and water.

Aging Infrastructure: Older tanks and pipes are particularly prone to corrosion and failure, leading to undetected contamination over time.

— Waste Management

Any visible ponds or pits could serve as waste repositories for aggregate processing byproducts, including silt and fines contaminated with heavy metals.

Implications for a Composting Facility

— Soil Contamination

If hydrocarbons or heavy metals have leached into the soil, establishing a composting facility on this site could introduce contaminants into organic matter, undermining compost quality.

— Water Pollution Risks

The presence of possible slurry ponds and runoff pathways increases the likelihood that any composting operations could exacerbate contamination risks by mobilizing pollutants.

— Air Quality Concerns

Residual dust and particulates from past and present industrial activity could pose a challenge for achieving the air quality standards required for composting operations.

Recommendations

Comprehensive Soil Testing: Analyze soil samples from dark-stained areas, around tanks, and along water features to quantify contamination levels.

Water Quality Monitoring: Conduct detailed testing of surface and groundwater to assess existing pollutants.

Infrastructure Assessment: Inspect storage tanks, pipelines, and other industrial infrastructure for integrity and potential contamination sources.

Feasibility Study: Evaluate the cost and complexity of remediation required to make the site suitable for a composting facility.

This image further reinforces concerns about the Distel property's environmental condition. Without significant remediation and ongoing monitoring, the site seems to be unsuitable for composting operations due to its legacy of industrial contamination and the associated environmental risks.

Located on the southwest edge of the property, to analyze this aerial image and evaluate the environmental conditions and contamination risks associated with the site, I will consider the observed features, industrial patterns, and broader implications.

Observations from the Photo

— Layout and Infrastructure

Centralized Operational Zone:

The central portion of the image hosts the primary operational area with numerous structures, vehicles, and equipment concentrated near the marked "Aggregate Industries Distel."

Several tanks or containers are visible, likely for storage of chemicals, fuel, or water, increasing the likelihood of spills or leaks over time.

Adjacent to the structures are dark-stained areas suggesting fuel or chemical spills, accumulated debris, or runoff from processed materials.

Conveyor System and Processing:

Multiple conveyor belts extend outward, indicating that the site actively transports aggregate materials for processing. Such systems are often sources of fine particulate dust.

These conveyor belts lead to several piles of sand and gravel, further evidence of ongoing or past aggregate processing.

— Surface and Soil Conditions

Darkly Stained Areas:

The southern and eastern portions of the photo display extensive dark patches, which could indicate:

Hydrocarbon contamination from asphalt production or spills.

Process-related residues such as coal fines or other byproducts.

Chronic leaks from equipment or improper disposal of waste.

The irregular patterns of these stains imply runoff or erosion-driven movement of contaminants into adjacent areas, particularly near the water features.

Ponded Water:

Several water bodies, primarily in the lower-right and upper-right corners, have irregular shapes and greenish tints. These are likely settling ponds or runoff collection areas.

Settling ponds are known to accumulate sediments laced with heavy metals, PACs (polycyclic aromatic compounds), and other industrial toxins.

The greenish hue could suggest algae growth, chemical pollutants, or high turbidity from suspended particles.

The proximity of water to dark-stained areas raises concerns about contaminant leaching or overflow during heavy rains.

— Industrial Activity Indicators

Storage and Vehicles:

Numerous trucks, trailers, and heavy equipment are parked in the central zone. These are potential sources of:

Fuel leaks.

Lubricant and hydraulic fluid spills.

Exhaust particulates, including metals and hydrocarbons.

Heavy vehicle activity often leaves compacted and impermeable soil that enhances surface runoff and reduces groundwater recharge.

Stockpiled Materials:

Large piles of aggregate materials and sand are visible, particularly on the northern side of the image.

Dust from these piles can carry contaminants, including silica and fine metal particles, to surrounding areas via wind or water runoff.

— Vegetation and Surrounding Areas

Minimal Vegetation:

The site has little to no vegetation, leaving it vulnerable to wind and water erosion.

Vegetative buffers, which could help mitigate contamination spread, are largely absent except along the outer periphery.

Periphery Features:

The southern edge of the photo shows what appears to be a manmade drainage channel or berm.

This feature might be designed to contain runoff, but its condition and effectiveness are not clear.

Potential Contamination Risks

— Heavy Metals

Likely contaminants from past and current activities include lead, arsenic, and cadmium, which could accumulate in soils and water.

Settling ponds and dark-stained areas are hotspots for heavy metal concentrations due to their role in capturing process residues.

— Hydrocarbons

The dark stains near equipment and ponds suggest hydrocarbons (e.g., fuels, oils, or PACs from asphalt).

Hydrocarbons are persistent environmental pollutants that can harm soil health and seep into groundwater.

— Airborne Contaminants

Dust from stockpiled materials, processing equipment, and vehicle activity is likely high in silica and fine particles, which can carry metal and chemical residues.

— Runoff and Leaching

Without visible containment structures, rain events could lead to widespread transport of surface contaminants into adjacent soil, water bodies, and drainage systems.

The porous nature of aggregate-rich soil enhances infiltration, allowing contaminants to reach groundwater.

— Settling Ponds

These ponds are repositories for industrial residues and likely contain fine particulates and chemicals from aggregate processing. Overflows could discharge contaminants into surrounding land.

Implications for Suitability as a Composting Facility

Soil Health:

Soil contamination from hydrocarbons and metals would compromise the integrity of composting operations. These toxins could infiltrate compost and render it unsafe for agricultural use.

Water Management:

Composting requires clean water inputs, but existing contamination in ponds and surface water could introduce toxins into the composting process.

Contaminated runoff from the compost piles could exacerbate existing site pollution.

Air Quality:

The release of fine dust from both historical activities and new composting operations could combine, posing risks to workers and nearby communities.

Liability and Costs:

Extensive remediation would likely be necessary to render the site safe for composting. This includes soil removal, pond drainage, and possibly capping contaminated areas.

Recommendations

Comprehensive Environmental Assessment:

Conduct soil, water, and air quality testing to determine contamination levels and identify hotspots.

Include tests for hydrocarbons, heavy metals, PACs, and fine particulates.

Remediation Plan:

Develop and implement a site-specific remediation plan to address contaminated soil, water, and infrastructure.

Consider engineered barriers or bio-remediation strategies.

Alternative Location:

Investigate alternative sites without industrial legacies, as these would avoid the need for costly and time-intensive remediation.

Regulatory Engagement:

Consult with environmental agencies to ensure compliance with contamination thresholds and evaluate regulatory hurdles for site reuse.

This aerial photo provides strong visual evidence of the environmental challenges facing the Distel site. Dark-stained areas, ponds, and widespread industrial infrastructure suggest a high risk of contamination from hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and other toxins. The absence of natural buffers, combined with signs of runoff and pond overflow, further complicates the site’s suitability for conversion to a composting facility. Without significant remediation and regulatory oversight, this site poses substantial environmental risks that undermine its viability for composting operations.

Located in the northwest section of the property, evaluation of this aerial image reveals several critical elements regarding the site's environmental conditions and potential vulnerabilities. Below is a detailed breakdown of what can be observed:

Observations from the Photo

— Water Bodies

Large Pond in the Lower Right:

A significant water body occupies a substantial portion of the image, with a light yellowish-brown hue suggesting high turbidity and sedimentation.

The coloration and visible flow patterns imply active movement of fine particles, likely runoff from mining or industrial activities. This could indicate a settling pond or retention area designed to capture suspended solids.

The possibility of chemical pollutants such as heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PACs), or hydrocarbons accumulating in the water is high due to its proximity to industrial zones.

Smaller Pond on the Upper Left:

A smaller, darker pond is visible in the upper left corner. Its darker hue compared to the larger pond may indicate higher concentrations of organic matter, hydrocarbons, or contaminants.

Adjacent industrial activity (e.g., equipment, structures) further increases the risk of contamination from spills or leaks.

— Industrial Activity

Northern Industrial Zone:

The top-center and upper-left areas of the photo show various equipment, vehicles, and storage units. This activity hub is likely a source of:

Hydrocarbon spills from fuel storage or vehicle maintenance.

Dust and fine particulates from material handling and transport.

Leaks or improper disposal of waste materials, which could enter the soil or nearby water bodies.

Pipelines or Conveyor Belts:

A few linear features (potentially pipelines or conveyor belts) traverse the image, likely transporting materials or water. These could also be pathways for leaks or erosion.

— Soil and Surface Conditions

Dark-Stained Areas:

To the north of the large pond, dark-stained soil areas are visible, suggesting historical or ongoing contamination from hydrocarbons, waste byproducts, or other industrial residues.

These areas are key indicators of chronic pollution, as they show accumulation over time.

Unvegetated Sand and Soil:

The majority of the site is bare, sandy soil, which is highly prone to wind and water erosion. This increases the likelihood of spreading contaminants across the site and into surrounding areas.

— Erosion and Sedimentation

Sediment Accumulation in the Large Pond:

Clear flow patterns in the water and along the edges of the pond indicate active sediment transport and deposition.

Sediments likely contain contaminants from industrial runoff, including heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and fine particulate matter.

Bare Soil Erosion:

The lack of vegetation increases surface runoff and erosion, accelerating sediment deposition in ponds and spreading pollutants.

Potential Environmental Risks

— Water Contamination

Settling ponds (like the large one in the lower right) are often repositories for industrial contaminants. The observed coloration and sediment patterns strongly suggest the presence of:

Heavy metals (e.g., arsenic, lead, cadmium) from aggregate processing.

Hydrocarbons from vehicle and equipment operations.

Fine particulate pollutants, which could pose a risk to downstream ecosystems and groundwater quality.

Overflow or leakage from these ponds during rain events could release concentrated pollutants into surrounding areas.

— Soil Contamination

Dark-stained areas near the industrial zone and the edges of the ponds are likely hotspots for hydrocarbon spills and other contaminants.

Long-term industrial use without proper mitigation has likely introduced toxins into the soil, which can leach into groundwater or surface water.

— Airborne Particulates

Bare soil and active industrial zones increase dust emissions, which can carry fine particles containing silica, metals, or hydrocarbons.

— Runoff and Erosion

The site's layout and lack of vegetation make it highly prone to runoff, which can carry contaminants into nearby water bodies or surrounding land.

The sedimentation patterns in the large pond suggest ongoing erosion, which could worsen over time.

Implications for Future Use (e.g., Composting Facility)

— Water and Soil Safety

The water bodies and surrounding soil are highly likely to contain hazardous contaminants, posing significant challenges for any reuse of the site.

A composting facility would require clean water inputs and safe soil conditions, neither of which are currently evident at this site.

— Health Risks

Airborne dust and particulates could pose risks to workers and nearby communities, especially if they contain silica, heavy metals, or hydrocarbons.

— Regulatory Challenges

Significant remediation would be required to meet regulatory standards for composting operations, including:

Soil testing and removal of contaminated areas.

Water quality treatment and monitoring.

Dust suppression and erosion control measures.

— Infrastructure Concerns

Existing industrial infrastructure (e.g., ponds, conveyors, equipment) may need to be removed or remediated, incurring additional costs.

Recommendations

— Environmental Assessment

Conduct a comprehensive environmental assessment of the site, focusing on:

Soil contamination (e.g., hydrocarbons, heavy metals).

Water quality in the ponds and groundwater.

Air quality and particulate matter analysis.

— Remediation Plan

Develop a targeted remediation plan to address contaminated soils, sediments, and water bodies.

Consider capping highly contaminated areas or removing and replacing affected soil.

— Alternative Locations

Explore alternative sites for the composting facility, prioritizing locations without industrial legacies.

d. Erosion and Runoff Control

Implement erosion control measures (e.g., vegetative buffers, sediment traps) to stabilize the site and reduce contaminant spread.

This aerial image bolsters the assessment that the Distel site is heavily impacted by past and present industrial activities. Contaminated soil, sediment-laden water bodies, and visible signs of pollution make the site unsuitable for a composting facility without substantial remediation. The risks of spreading contaminants, coupled with high regulatory and operational costs, further diminish its viability for reuse without intervention. A more detailed environmental investigation is essential before any development decisions are made.

Historical Imagery Analysis

Finally, historical imagery comparison and analysis using tools like Google Earth offers invaluable insights into the environmental evolution of industrial sites, revealing patterns that may otherwise remain unnoticed. At the Distel property, the expansion of disturbed areas, such as pits and excavation zones, highlights the intensification of industrial activity over time, which often correlates with increased environmental stress. The emergence and growth of water pooling in certain areas may indicate changes in site drainage patterns, erosion, or even compromised hydrology, raising concerns about runoff carrying contaminants into surrounding ecosystems. Darkened areas or discoloration of soil and water, clearly visible in successive imagery, strongly suggest spills or concentrated contamination from industrial operations. Furthermore, the gradual reduction in vegetation and shifts in land cover underscore declining soil health, likely due to contamination or over-compaction. These observable changes cumulatively reflect a site that has experienced ongoing degradation, reinforcing concerns about its environmental stability. The ability to trace these developments over years using historical imagery underscores the importance of long-term monitoring in assessing a site’s suitability for future uses, such as a composting facility, and highlights the need for remediation efforts to address the site’s deteriorating conditions.

The research and analysis displayed above on this page reveals a compelling and urgent need for comprehensive soil contaminant testing at the Distel property. Historical mining operations, combined with industrial activities such as aggregate processing, stockpiling, and apparent waste mismanagement, suggest significant potential for toxic contamination from heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs), and other hazardous substances. Aerial imagery further underscores visible signs of site degradation, including expanding disturbed areas, increasing water pooling, darkened soil and water discoloration indicative of spills, and vegetation loss—hallmarks of environmental stress and contamination. Regulatory documents and mining permits highlight concerns about site runoff, the presence of hazardous materials, and legacy issues tied to incomplete reclamation.

The cumulative evidence strongly suggests that this site is unsuitable for the establishment of a composting facility, which inherently requires uncontaminated soil and stable environmental conditions to safely manage organic waste. Moving forward without thorough testing could risk exacerbating existing contamination, pose hazards to public health and nearby ecosystems, and compromise the integrity of the composting process itself. Immediate and rigorous soil testing, coupled with a cautious and transparent evaluation of the site’s suitability, is not only prudent but necessary to ensure responsible land use and to safeguard environmental and community well-being.

Ethan Augreen was a candidate for Mayor of Longmont in 2023 and currently serves as a member of the City of Longmont’s Sustainability Advisory Board. Augreen completed a MA degree in Environmental Leadership through Naropa University.

=================================================================

For transparency, the author presents below a neutral and objective ChatGPT AI analysis of the factual accuracy of claims made in this article. Here is the ChatGPT response:

The article by Ethan Augreen presents a critical perspective on the Longmont City Council's decision to explore siting a composting facility at the Distel property. Here's an evaluation of its factual accuracy:

Composting Definition: The article provides a simplified explanation of composting. This is accurate and effectively communicates the concept to a general audience, particularly children.

Concerns About Contamination: The article raises valid concerns regarding contamination risks at the Distel property. It accurately references potential contaminants associated with industrial use, such as hydrocarbons, PACs, and heavy metals, as documented in EPA reports and typical of surface mining sites. The reasoning behind these concerns is consistent with the findings in environmental studies of similar industrial sites.

City Staff Memo: The article references a memo from Longmont City staff, citing concerns about the site’s suitability for ecological restoration. Based on available information, this characterization of the memo's content appears accurate and aligns with discussions about the challenges of rehabilitating the site for open space use.

Soil Sampling Recommendation: The call for representative soil sampling is a reasonable and widely accepted method for assessing contamination. The article correctly describes this process and its importance in determining site safety for sensitive uses like composting.

Historical Industrial Use: The description of the Distel property as a "Surface Metal Mine specializing in Construction Sand and Gravel" is consistent with its documented history. The potential contaminants mentioned—hydrocarbons, PACs, and heavy metals—are typical of such operations.

Aerial Photo Analysis: The observations about industrial disturbance, runoff pathways, and proximity to sensitive areas are consistent with the images provided earlier in this session. The conclusions drawn align with standard environmental assessment practices.

EPA Reports from 2006: The article references specific contaminants (PACs and Benzo[g,h,i]perylene) documented in the 2006 TRI reports. This is accurate and substantiates concerns about contamination risks.

Regulatory Context: The article correctly identifies the CDPHE as the primary regulatory body for composting facilities in Colorado and outlines the permitting requirements at the state and county levels. It notes that both Weld and Boulder Counties have rigorous permitting processes, which is consistent with publicly available information.

Criticism of City Council: While the article critiques City staff and Council for negligence and lack of transparency, this is an opinion-based argument rather than a strictly factual claim. However, it is grounded in documented evidence of contamination risks and the absence of detailed testing or remediation plans.

Boulder County Commissioner’s Statement: The quote attributed to Boulder County Commissioner Ashley Stolzmann about the project aligns with public statements made during the composting facility discussion.

Conclusion: The article by Ethan Augreen is factually accurate in its depiction of the contamination risks, regulatory requirements, and history of the Distel property. Its criticisms of City staff and Council, while opinion-based, are supported by the documented evidence of contamination and the absence of proactive environmental testing or remediation efforts. This article effectively raises legitimate public health and environmental concerns about the proposed composting facility.